Given the cataclysmic battles taking place in Ukraine and Gaza, the extraordinary impact those conflicts are having on the innocent citizens caught up therein are causing emotions to run high. Both wars are unfolding catastrophes, amplified by the immediacy of the documentary evidence of suffering, loss and destruction. Last week, to inform and advise my staff returning from half term, I wrote the following commentary to them:

“Education Secretary Gillian Keegan, the Minister for Schools and the Minister for Skills have written to schools and colleges on 17 October 2023 to provide advice on how to respond to the Israel-Hamas conflict in the classroom – you can find that advice here.

Over the half-term break, our own community leaders covering the faith represented in the war, Imam Abid Hashmi, Rabbi Dr Jonathan Romain and Reverend Sally Lynch all met at Maidenhead Mosque to each read a prayer for peace from their own tradition. I attach the newspaper article covering that appeal, and I quote one element from that which covers our needs so well, that by Imman Hashmi: “[We said] not to let that disturb our peace here in our Maidenhead community. No matter what happens over there, here, Jews, Muslims, Christians, we are all brothers,” he said.

Clearly we will have members of our school caught up in this conflict, and some I fear directly with the loss of loved ones in Israel and Gaza. In addition, we have in our midst 12 Ukrainian children and young people, for whom war back home remains a lived reality. With such conflicts in mind, the DfE produce additional guidance and support last year, to help teachers and schools navigate issues such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the legacy of the British Empire or societal responses to racism in accordance with the law. We recognise that teachers must not promote partisan political views and should offer a balanced overview of opposing views when political issues are taught, and it is certainly important we keep well clear of the toxic comments and expressions of hatred visible on social media, consumption of which will herald no victory!“

This Sunday heralds the arrival of Remembrance events across the nation, led by the central National Service of Remembrance to be held at the Cenotaph on Whitehall, London. Starting at 11am, the service will commemorate the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women involved in the two world wars and later conflicts. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport coordinates the event, alongside colleagues from across government, the armed forces and veterans’ organisations. Those more recent conflicts, particularly in Iraq and Afghanistan have renewed our nation’s focus on the loss to parents, wives and husbands, children and family and there is no doubt that the nature of the services is to focus on that sense of loss in the cause of heroic service by serving military, called to action by their country, our nation, the United Kingdom.

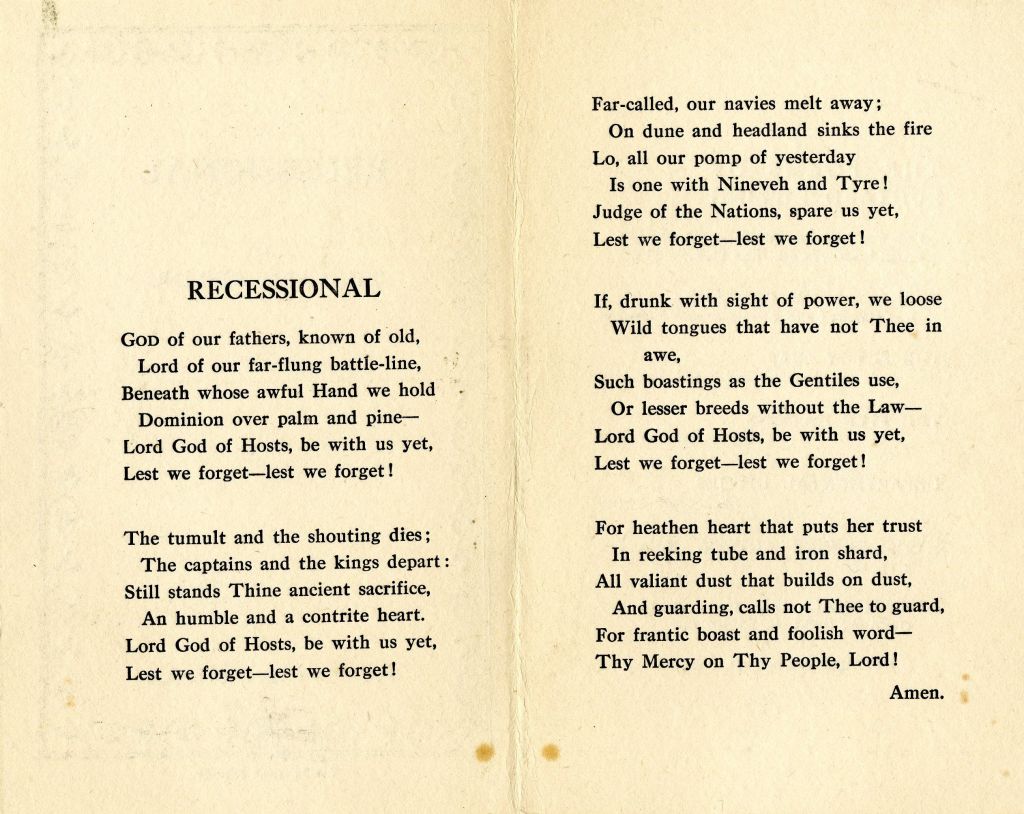

The phase ‘Lest we forget’ predates the First World war by many years, written first by one of our country’s greatest poets, Rudyard Kipling, coming from his poem ‘Recessional’, written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, published 17 July 1897. I’ve posted the full poem at the close of this blog, and Wikipedia’s excellent short commentary describing the poem has this to say:

“Initially, Kipling had not intended to write a poem for the Jubilee. It was written and published only towards the close of the Jubilee celebrations, and represents a comment on them, an afterword. The poem went against the celebratory mood of the time, providing instead a reminder of the transient nature of British Imperial power. The poem expresses both pride in the British Empire, but also an underlying sadness that the Empire might go the way of all previous empires. The title and its allusion to an end rather than a beginning add solemnity and gravitas to Kipling’s message. In the poem, Kipling argues that boasting and jingoism, faults of which he was often accused, were inappropriate and vain in light of the permanence of God.”

From the outbreak of the First World War, Kipling wrote propaganda for the British government and as an expression of his patriotism managed to persuade the military authorities to permit his son John, initially rejected for service because of poor eyesight, to be commissioned as a second lieutenant into the 2nd Battalion, Irish Guards on 15 August 1914, two days before his seventeenth birthday. Not 6 weeks later, John was reported injured and missing in action during the Battle of Loos, and despite the frantic searches of both parents, John’s body was not found. Rudyard became involved with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and wrote as an epitaph “If any question why we died, / Tell them, because our fathers lied.” It’s perhaps nice that in 1992, the same Commonwealth War Graves Commission discovered a mistake in the paperwork and identified his grave changing an inscription on the gravestone of an unknown soldier to read John Kipling, which lies in the St Mary’s ADS Cemetery in Haisnes.

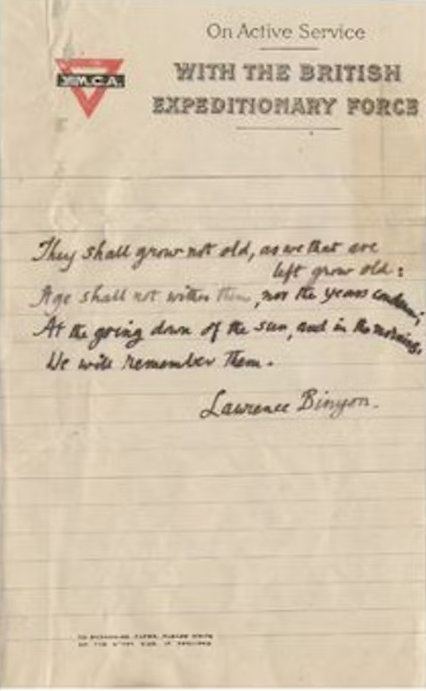

Kipling used his powerful writing at the time to validate another poet’s words, those of Laurence Binyon. Right from the start of the Great War in 1914, long lists of the dead and other casualties were appearing in newspapers, and looking at across the sea in Cornwall, Binyon composed nded were appearing in British newspapers. With the British Expeditionary Force in retreat from Mons, promises of a speedy end to war were fading fast.

Against this backdrop Binyon, then Assistant Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, sat to compose “For the Fallen”, a poem that Rudyard Kipling would one day praise as “the most beautiful expression of sorrow in the English language”.

Whilst the 11th hour of the 11th Day of the 11th Month of 1918 was when the fighting stopped with the signing of the armistice by the allies and Germany, the war itself continued into 1919 until the signing of the peace treaty of Versailles on 19 June 1919. There was nothing neat about the close of that war, and the ensuing months and years that followed saw continued suffering and misery across Europe. On On 14 May 1921, the various associations that provide diverse support for the surviving military ex-servicemen chose to come together and the Royal British Legion was formed, who oversee this charitable work to the present day.

The following statement comes from their website today and it makes a defining statement of the purpose for Remembrance:

Remembrance honours those who serve to defend our democratic freedoms and way of life.

We unite across faiths, cultures and backgrounds to remember the service and sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. We will remember them.

- We remember the sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from United Kingdom and the Commonwealth.

- We pay tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- We acknowledge innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

Wearing a poppy is is never compulsory but is greatly appreciated by those who it is intended to support. When and how you choose to wear a poppy is a reflection of your individual experiences and personal memories.

Remembrance unites people of all faiths, cultures, and backgrounds but it is also deeply personal.

It could mean wearing a poppy in November, before Remembrance Sunday. It could mean joining with others in your community on a commemorative anniversary. Or it could mean taking a moment on your own to pause and reflect. Everyone is free to remember in their own way, or to choose not to remember at all.

To conclude the point I have been illustrating, Remembrance as both a process have been deeply woven into the British and Commonwealth’s psyche for over a century, and unlike most other services covers all faiths and none. As child, the old, injured and invalided ex-servicemen from the legion wore their medals with pride and by engaging with them though the purchase of a poppy we felt we assisted in obeying Kipling’s warning, Lest we forget, obey Binyon’s instruction “We will remember them” and concur with that witness articulated by Kipling that it was his lies that killed his son. So many young men went to war willingly, not knowing the horrors soon to befall them, and the catastrophic effect on all the countries involved must not be forgotten. 25% of entire military population of France was lost, that’s 1.3 million men, exceeded only by Russia with 1.8 million, with Britain & empire not far behind with 913,00 (715,000 UK, 198,00 dominions).

The ghastliness of both conflicts in Ukraine and Israel cannot be underestimated, indeed barely comprehended at present, but whatever views we might have about the various legitimacies of action, we are surely best off keeping those views separate from the genuine and solemn purpose Remembrance has at the heart of our national life in Britain. Kipling’s Recessional below mourns the passing of our Empire 120 years and more ago, but those in Empire did not let us down in the 14-18 war. Year 9 boys and girls in our school last month have been studying in depth the contribution made by the Hindu and Urdu populations of the Indian sub-continent, as well as those from the other dominions too; neither would really have understood the Christian prayer-type structure of the poem, but they truly understood and honoured the loyalty they felt for our King and country, and over 1.3 million gave service during the war across all arenas, from the Western Front, Turkey, Iran (to protect our oil fields), Egypt, its own frontiers with its neighbours, Singapore and China. In teaching this history in school, we bring to the attention of the next generation the knowledge and understanding of the past, by writing an assessment on same, we test their knowledge and help embed the memory in their consciousness that the Great War took place, and left nobody across the world in any doubt of the subsequent devastating effect of war.

Remembrance does not glorify war and its symbol, the red poppy, is a sign of both Remembrance and hope for a peaceful future.