This week’s blog explains why it’s easier to make some stuff up rather than go by the evidence!,” discusses the prevalence of educational myths, contrasts them with evidence-based approaches, and features the career insights of World champion & Olympic bronze medallist Mark Richardson, Claires Court Headboy in 1987-1988.

As a professional teacher, growing up through more than the average number of decades than most, I’ve seen a ‘Heinz variety’ of Edu-myths, promoted to be kind to adults and children, on why perhaps their ‘intelligences’ were maybe different to others in the same context, and how perhaps they might be better attuned to learn differently.

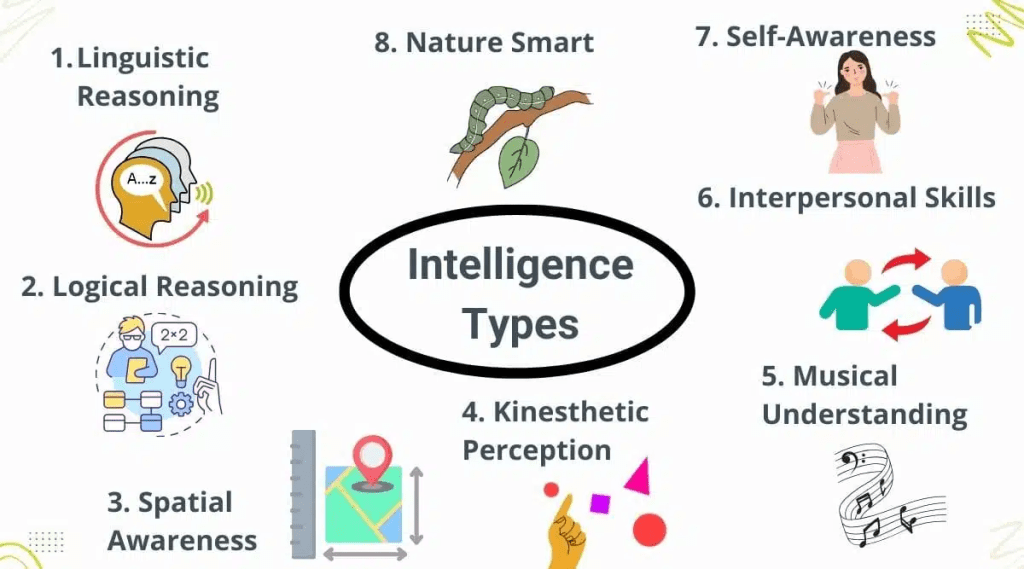

The graphic below shows categories of intelligence types, yet have no scientific basis whatsoever:

Howard Gardner started this ‘Goldrush’ in the early 1980s with his ‘multiple intelligences’ model, which grew up alongside the much-promoted concept of ‘learning styles’. Other myths include the VARK model, that learning is better in bite-sized chunks, that left-brain/right-brain dominance dictates how people learn, and that a specific amount of learning (20% in this case) is lost when ‘students’ sleep. As the graphic above shows, it makes such good points that ‘surely it must be true?’ Sadly not, there’s no golden ticket to the future, just the bitter Northern Irish truth that ‘Life is hard and then you die’, perhaps even better illustrated by American Science Fiction writer David Gerrold, who wrote:

“Life is hard. Then you die. Then they throw dirt in your face. Then the worms eat you. Be grateful it happens in that order”

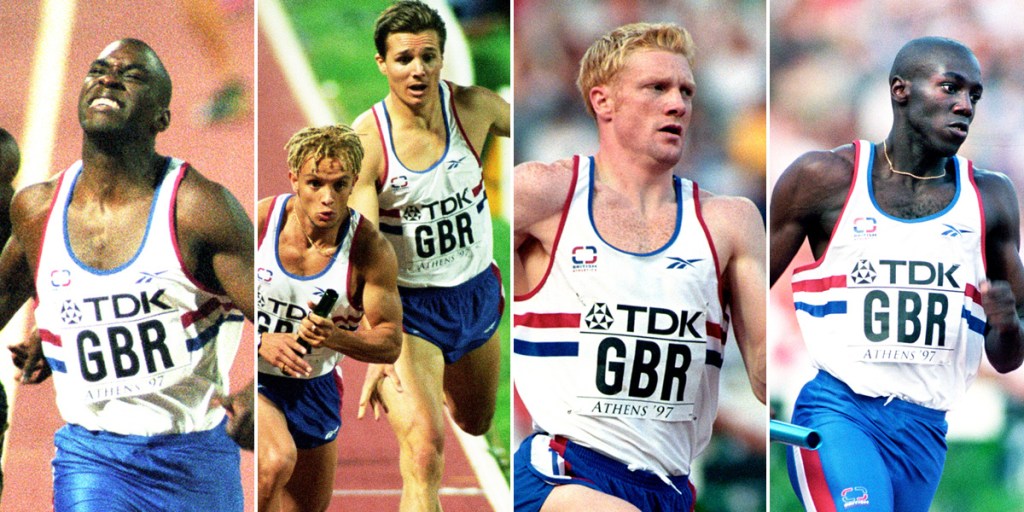

Our first visitor in our Speaker series this year was the athlete Mark Richardson (1983-88), Olympic medallist and World Champion and last Friday night, his 45 minute or so unscripted talk highlighted much about his development as a teenager into adulthood and his learning as an elite athlete that rang so true of what I remember about Mark in the 5 years he was at Claires Court. To an audience of parents and their sporty offspring, Mark’s presentation included his development from wannabe runner through the 1990’s culminating in his ‘greatest race’, winning the 1998 400m against Michael Johnson, world champion at the time.

In the 1997 World Championsips, Mark ran the anchor leg of the 4x400m relay, and initially won the Silver medal behind the USA quartet, subsequently upgraded to Gold when one of the American runners admitted to doping offences. Mark was asked whether he minded having to wait until this July to receive his medal, with the other 4 involved, Jamie Baulch, Roger Black, Iwan Thomas and heat runner Mark Hylton.

Mark’s reply was simply wonderful. “Not at all. This time, in the London stadium, my daughters were present. So for them, Dad wasn’t just somebody who’d been an athlete long ago, before they were born. To have my medal presented to me and the team, whilst their mum and they watched was a magical moment’.

After his athletics career, and a period of self-doubt and reflection, Mark commenced on a career in business.

“ I now consult with organisations and I take a lot from being an athlete and setting performance goals, deconstructing things into thinking about what it is you’re trying to achieve, thinking about those performance milestones, those key performance indicators, and then breaking it down into bite-sized chunks that you can be doing, day in and day out.

I’m a big believer in that. I learned that skill as an athlete – and the ability to compartmentalise as well. There are loads of things I probably didn’t realise that I was doing 30 years ago as an athlete, but I’ve got the benefit of really strong knowledge about performance psychology now.”

What Mark made abundantly clear to us is that, to reach the very top, you need to have that as the goal, and you have to believe in yourself and your capabilities to improve. It is best not to spend any time dwelling on what others do, but to look after your own ambitions and then break them down into clear, compartmentalised goals, each of what are supported by specific tasks to do and changes in training so achieve them. He highlighted the many setbacks he faced throughout his running career, most notably that overtraining led to burnout and viral illness. During the audience’s opportunity to question Mark, they asked whether he ever ran that fast in training. Somewhat disarmingly, he answered, “I’m quite a lazy trainer and I’d never try that hard in training, just jog around, sort of faking it!”

All the signs are that, for whatever learning and skill acquisition needs to be completed, the support that fails is that of undeserved praise. Rather than suggesting someone is brilliant, what is much more effective is to check on what went well, highlight possible next steps and allow for feedback and goal setting.

I conclude this blog by quoting from a very recent article by Professor Carl Hendrick, formally an English teacher locally, and fellow researcher into what works best in learning: “The comfort of myth crowds out the discipline of truth (even amongst teachers):

This is not science. It is not even good pedagogy. It is moral theatre, performed for an audience of educators who want to believe they are doing the right thing without having to prove it. And the applause comes not from improved student outcomes, but from the warm glow of shared moral conviction.

The great danger of comfortable fictions is not that they are wrong, but that they make us feel right. They provide the satisfaction of moral certainty without the inconvenience of empirical accountability. They allow us to believe we are helping when we may be harming, to think we are progressive when we may be perpetuating the very inequalities we claim to oppose.”