Early March saw our IGCSE results in English and Maths released from the January series of examinations, for many Year 11 pupils this being their introduction into the suite of exam finals they are to take in May and June. Results were as you would expect a mixed bag, because that’s indicative of our broad ability intake, but with A* and As abounding it’s a reminder to all that for many terminal exams without coursework are a ‘good thing’.

Early March saw our IGCSE results in English and Maths released from the January series of examinations, for many Year 11 pupils this being their introduction into the suite of exam finals they are to take in May and June. Results were as you would expect a mixed bag, because that’s indicative of our broad ability intake, but with A* and As abounding it’s a reminder to all that for many terminal exams without coursework are a ‘good thing’.

The IGCSE examinations themselves have been around for 30 years, introduced at the same time as the England & Wales based GCSEs, and replaced the old O levels and CSE examinations. The new home-based GCSEs had large elements of coursework, indeed English was permitted to move to 100% coursework in the early years. Verification and validation of coursework marking were managed by examiner visits and representative sampling of exam scripts, which were sent direct to the exam boards. IGCSEs were developed to be sat all over the world, but it was clearly impractical to send examiners from England to local centres abroad, and so the IGCSE started and have remained as courses supported by terminal examinations only. Inevitably, the exponents of the new style of course with more coursework and less examination considered the new GCSEs better, as the graduating students were made more aware of what they knew, understood and could do through the 2-year educational process. Graduates of the terminal exam process never had the opportunity to ‘improve’ their work over the 2 period of study, so had to be good enough in one hit, so to speak.

The immediate effect of the new GCSE courses was that children’s  school achievement dramatically improved, with so many top level grades being achieved by the students, released from the stifling effect of the old terminal examination test of knowledge (the old O level). With impressive efficiency, teachers learned what the systems were to maximise best effect coursework, and results continued to improve through the 1990s and ‘noughties’. Sadly, whilst results improved, the actual literacy, numeracy and skill-base in 16 year old pupils did not improve, as seen by Sixth Forms, Universities and Employers alike, so the suspicion of ‘gaming’ even ‘cheating’ the system grew in the onlookers’ minds. 10 years or more ago, to counteract this ‘problem’, coursework was swapped out for ‘controlled assessments’, min-public exams during the 2 year GCSE programme, which would solve the perceived woes of coursework. Job done, verification and validation swapped out for external marking, and public confidence in the GCSE exam process restored.

school achievement dramatically improved, with so many top level grades being achieved by the students, released from the stifling effect of the old terminal examination test of knowledge (the old O level). With impressive efficiency, teachers learned what the systems were to maximise best effect coursework, and results continued to improve through the 1990s and ‘noughties’. Sadly, whilst results improved, the actual literacy, numeracy and skill-base in 16 year old pupils did not improve, as seen by Sixth Forms, Universities and Employers alike, so the suspicion of ‘gaming’ even ‘cheating’ the system grew in the onlookers’ minds. 10 years or more ago, to counteract this ‘problem’, coursework was swapped out for ‘controlled assessments’, min-public exams during the 2 year GCSE programme, which would solve the perceived woes of coursework. Job done, verification and validation swapped out for external marking, and public confidence in the GCSE exam process restored.

Except not quite, for the public exam bodies started noting that individual exam centres had continued to make further, sometimes rather too dramatic improvements for their students. Anecdotal evidence emerged about children being placed in classrooms and asked to copy down answers from the board, and whistle blowers in schools started to write about the blatant cheating taking place. Here’s an article from the Secret teacher published in the Guardian in June 2015 “Controlled assessments are not properly scrutinised by line managers and exam boards, a problem that gets worse every year. More and more teachers allow students to use extensive written notes when only limited prompts are allowed. In April I found students in the library “redrafting” controlled assessments for the sixth or seventh time when they should not be attempted more than once.”

Except not quite, for the public exam bodies started noting that individual exam centres had continued to make further, sometimes rather too dramatic improvements for their students. Anecdotal evidence emerged about children being placed in classrooms and asked to copy down answers from the board, and whistle blowers in schools started to write about the blatant cheating taking place. Here’s an article from the Secret teacher published in the Guardian in June 2015 “Controlled assessments are not properly scrutinised by line managers and exam boards, a problem that gets worse every year. More and more teachers allow students to use extensive written notes when only limited prompts are allowed. In April I found students in the library “redrafting” controlled assessments for the sixth or seventh time when they should not be attempted more than once.”

The elements of the above have led to huge volumes of conflict within the profession, creating a real sense of Cognitive Dissonance for all. In many schools it seems, with the endless raft of assessment going on, the most effective way to ensure the best outcomes for the children was to enable them to cheat – “Out the window with Integrity” said one type of teacher – “I get my *performance bonus*, the children get their grades, what’s to worry?”

The Government felt it had to act, and called for the cancelling of all controlled assessments, and the new terminal examination GCSEs are rolling out in schools, with English, English Literature and Maths arriving this Summer in new terminal form, together with new number values (1-9) to replace the former letter grades (G-A*). By the Summer of 2019, all the old GCSEs will have been consigned to the scrap bin, and the opportunities for teachers to ‘cheat ‘ removed. Hoorah say one and all.

The Government felt it had to act, and called for the cancelling of all controlled assessments, and the new terminal examination GCSEs are rolling out in schools, with English, English Literature and Maths arriving this Summer in new terminal form, together with new number values (1-9) to replace the former letter grades (G-A*). By the Summer of 2019, all the old GCSEs will have been consigned to the scrap bin, and the opportunities for teachers to ‘cheat ‘ removed. Hoorah say one and all.

Many Independent schools, Claires Court included, found that they needed to move away from GCSEs with controlled assessments for other reasons, not least because the 110+ tests an average independent school child taking 10 GCSE were rapidly becoming almost all the child had time to do in the 2 year period. To be honest, as the course actually only covered some 60 weeks over the duration of the course, this made teaching all about the test and little else; failed ‘controlled assessments could be retaken, which only compounded the felony. A child receiving a ‘b’ as opposed to a ‘a*’ (lower case grades being the way these mini tests were reported) immediately encouraged taking the assessment an extra time, which meant even more sessions were lost to the test.

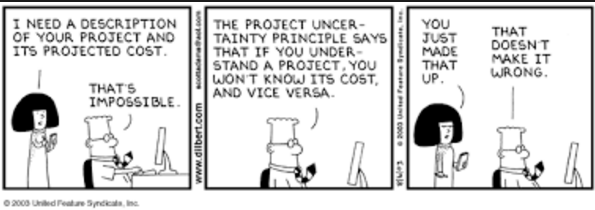

Fortunately, the GCSE world of controlled assessments has been short lived, and the new GCSEs feel very much like the IGCSEs that have continued to be sat throughout the intervening period. Teachers and pupils are having to learn/relearn how to teach and study for terminal examinations, with far fewer indicators available to determine progress along the way. It’s changing teacher and pupil work load too, because work covered previously has to be resurfaced and considered anew, in the light of the broader thematic considerations that can now be introduced into the testing process. Teachers probably have to be thinking all around the landscape, encouraging their students to do so too, because of course, we have absolutely no idea what questions will be set, or what the marking scheme will look like!!!

But the joy of all this uncertainty is that we will teach more effectively, the courses will be more creative and engaging; the children will genuinely feel (and we know this now because they are in Year 10) that school is more than just a series of interminable tests – actually we had broken away in about half-the subjects anyway, so even Year 11 feel they have had some time to be ‘free spirits’ with their learning. Whilst the changes do not guarantee ‘Excellent achievement for all’, they make the outcomes even more likely.

And finally, as an Independent school, because we are not constrained by DfE rules about who does what, we have IGCSEs and GCSEs in whatever mix we wish. Whatever type of GCSEs you take, we still have the issues of a mix of letters and numbers for a couple of years, so it doesn’t honestly matter whether you get a Letter grade or a Number value. Universities and Employers of course are going to see the mix of alphabet soup for years to come, and the confusion will last as long as it did when the old O levels and CSEs moved from numbers to letters back 40 years ago.

*Readers of A Principled View might be surprised to learn that the Principals of Claires Court do not offer performance based pay. We prefer to ensure our staff are well rewarded for their work and to ensure that if pay is to rise, it does for all.

As it happens, I have known Alastair Cooke for many years, from his previous professional life as the general Secretary of the Independent Schools Council. As soon as he read our submission in nomination of Todd for the award, he recognised the fact that Todd’s sister had received the same award 3 years previously

As it happens, I have known Alastair Cooke for many years, from his previous professional life as the general Secretary of the Independent Schools Council. As soon as he read our submission in nomination of Todd for the award, he recognised the fact that Todd’s sister had received the same award 3 years previously

Writing back in 2010, Michael Morpurgo has this to say about the critical need for a robust Arts education in schools: “I would like to propose that we let the imagination take its place at the heart of learning, and that we create a climate in which it can flourish. We need discovery; making; doing; exploring; creating; critical thinking; seeing; hearing; experiencing. Children have to be introduced to the arts in every form.” It’s almost the strapline for the Claires Court Learning Essentials, the approach we have developed since then for everything we do at school. Now on Tuesday this week, we see the publication of the

Writing back in 2010, Michael Morpurgo has this to say about the critical need for a robust Arts education in schools: “I would like to propose that we let the imagination take its place at the heart of learning, and that we create a climate in which it can flourish. We need discovery; making; doing; exploring; creating; critical thinking; seeing; hearing; experiencing. Children have to be introduced to the arts in every form.” It’s almost the strapline for the Claires Court Learning Essentials, the approach we have developed since then for everything we do at school. Now on Tuesday this week, we see the publication of the and whilst there may of course be plenty to shout about, not much of the mood music is positive. It’s dry January, nights are long, mornings still dark, weather still wintry and some big banks have announced they are relocating thousands of jobs from London to Europe. With the best will in the world, it is easy to understand why the news media can’t find too much good news to shout about.

and whilst there may of course be plenty to shout about, not much of the mood music is positive. It’s dry January, nights are long, mornings still dark, weather still wintry and some big banks have announced they are relocating thousands of jobs from London to Europe. With the best will in the world, it is easy to understand why the news media can’t find too much good news to shout about. Dear Reader, please believe me when I say that schools in the independent sector have almost no idea about the outcomes of such publications in any given year, other than that we are able to look up our data with 24 hours to go to see ‘what’s what’. Now the statistics are published, not only can any one go and look up the data, but they can make use of the government’s comparison tool to compare the performance of any schools they might wish. FYI, you can find that tool here:

Dear Reader, please believe me when I say that schools in the independent sector have almost no idea about the outcomes of such publications in any given year, other than that we are able to look up our data with 24 hours to go to see ‘what’s what’. Now the statistics are published, not only can any one go and look up the data, but they can make use of the government’s comparison tool to compare the performance of any schools they might wish. FYI, you can find that tool here:

this week. 3 sixth formers from their idyllic welsh valley in Pembrokeshire swapped for three days into two of the best schools in Seoul. Make no bones about it; on the face of what we witnessed, the city pupils in Gangnam had the better deal when it came to school results, but at what cost? School days for most seem to last for up to 18 hours, with only 6 hours for the children to ‘sleep’, no more. before remounting the treadmill for another day in their 44 weeks of school year. You can read a little more

this week. 3 sixth formers from their idyllic welsh valley in Pembrokeshire swapped for three days into two of the best schools in Seoul. Make no bones about it; on the face of what we witnessed, the city pupils in Gangnam had the better deal when it came to school results, but at what cost? School days for most seem to last for up to 18 hours, with only 6 hours for the children to ‘sleep’, no more. before remounting the treadmill for another day in their 44 weeks of school year. You can read a little more  Sian Griffiths’ worries are that if the South Koreans grab the best bits from our offer to children, such as our hands-on practical lessons in science or development of creative skills, they’ll not loose the academic advantage in hard maths and languages, and suddenly we’ll be exposed on all fronts as being second-rate and what little international successes we having will disappear completely. She makes a very valid point here, when she asks “and what lessons are we learning from the South Koreans?”

Sian Griffiths’ worries are that if the South Koreans grab the best bits from our offer to children, such as our hands-on practical lessons in science or development of creative skills, they’ll not loose the academic advantage in hard maths and languages, and suddenly we’ll be exposed on all fronts as being second-rate and what little international successes we having will disappear completely. She makes a very valid point here, when she asks “and what lessons are we learning from the South Koreans?” ally the story is much more complex. Here goes…

ally the story is much more complex. Here goes… return to ‘thinking’ after Boxing Day. The raw emotion sown in the title arises is me simply because so much has been traduced by a variety of governments over the past decade in the quest for progress for no good reason; and in educational terms that means for so many in schools and colleges, new amounts of work have been created through the imposition of structural change, and not just once or twice, in recent years. Let me give you a couple of examples.

return to ‘thinking’ after Boxing Day. The raw emotion sown in the title arises is me simply because so much has been traduced by a variety of governments over the past decade in the quest for progress for no good reason; and in educational terms that means for so many in schools and colleges, new amounts of work have been created through the imposition of structural change, and not just once or twice, in recent years. Let me give you a couple of examples. still, tying shoe laces, managing their own toileting are no longer expectations teachers can have for the new intake at aged 4. As a close friend and expert in children’s development, Professor Pat Preedy has this to say: “Children today are moving less, they’re developing less well, and they’re learning less; we need to do something drastic to make sure children now and in the future get the movement they need to develop properly physically, intellectually and emotionally.”

still, tying shoe laces, managing their own toileting are no longer expectations teachers can have for the new intake at aged 4. As a close friend and expert in children’s development, Professor Pat Preedy has this to say: “Children today are moving less, they’re developing less well, and they’re learning less; we need to do something drastic to make sure children now and in the future get the movement they need to develop properly physically, intellectually and emotionally.” change comes because England is seen to be doing less well in the international PISA tables than over European and Asian nations. But changing the structure for the entire country is completely counter-intuitive, because many of our schools are already matching or outperforming these other nations, as data released by OECD themselves makes clear. But change has happened across all the key stages, and we won’t be able to judge the efficacy of this change for many years to come – one good or bad set of results for the country can’t be used to prove anything, as research needs to be longitudinal and spread over 5 years at least. And it’s not just the toughening up of the core disciplines that’s the issue, but the narrowing of the curriculum with the loss of so many important supporting disciplines. With subjects such as Art, Design technology, Drama, Music and RS consigned to the perimeter in so many state schools, children won’t find out they have an academic interest in such disciplines in the same planned manner as before. None of these changes have to make an impact upon the independent sector in which I work; it’s noticeable though that there is an increasing sense of separation from our sector to mainstream, encouraged by government themselves, suggesting that we should be doing far more to influence and support education within the mainstream. David Hanson, CEO of IAPS pointed out recently that poor parents were put off by negative stereotypes of private schools; “The media characterisation of private schools is so extreme and embedded through constant repetition that for ordinary people what they represent is not only unattainable, but also incomprehensible and alien.”

change comes because England is seen to be doing less well in the international PISA tables than over European and Asian nations. But changing the structure for the entire country is completely counter-intuitive, because many of our schools are already matching or outperforming these other nations, as data released by OECD themselves makes clear. But change has happened across all the key stages, and we won’t be able to judge the efficacy of this change for many years to come – one good or bad set of results for the country can’t be used to prove anything, as research needs to be longitudinal and spread over 5 years at least. And it’s not just the toughening up of the core disciplines that’s the issue, but the narrowing of the curriculum with the loss of so many important supporting disciplines. With subjects such as Art, Design technology, Drama, Music and RS consigned to the perimeter in so many state schools, children won’t find out they have an academic interest in such disciplines in the same planned manner as before. None of these changes have to make an impact upon the independent sector in which I work; it’s noticeable though that there is an increasing sense of separation from our sector to mainstream, encouraged by government themselves, suggesting that we should be doing far more to influence and support education within the mainstream. David Hanson, CEO of IAPS pointed out recently that poor parents were put off by negative stereotypes of private schools; “The media characterisation of private schools is so extreme and embedded through constant repetition that for ordinary people what they represent is not only unattainable, but also incomprehensible and alien.” And therein lies the rub. State and Independent school curricula and provision are moving in very different directions indeed, driven by the turmoil of structural change in the state sector. The best state schools will attract and retain the highest quality staff, and be able to offer great breadth and diversity of choice, subject and extra-curricular activity. But those schools that are not able to cope with these demands of structural change, exacerbated by continuing and dramatic budget cuts each year, are having their governing bodies excised and school leaders dismissed at an ever increasing frequency. The net effect is high staff turnover, low aspiration in achieving anything outside of the explicit demands of the ‘test’ and a general lack of confidence that the school more generally can meet all of its pupils’ needs. Suggesting now, as the Government’s Green Paper (November 2016) does, that the way forward involves further dramatic structural change, leading to the expansion of grammar schools at the expense of the other existing schools losing their most able pupils in the process will clearly exacerbate the decline in confidence and breadth of success in such schools. It’s worth noting that in a previous structural change, government insisted Universities were better placed to run schools than local governing bodies. The experiment is only a few years old, but all the evidence indicates the experiment is not going well. Moreover, as Professor Louise Richardson Vice Chancellor of Oxford University has made clear; asking universities to set up free schools is “insulting” to teachers and heads. Speaking to the Today programme on 22 September 2016, Professor Louise Richardson said forcing her institution to establish schools would be a “distraction from our core mission”, and said universities already helped the schools community in many ways, but running them was “not what we do”.

And therein lies the rub. State and Independent school curricula and provision are moving in very different directions indeed, driven by the turmoil of structural change in the state sector. The best state schools will attract and retain the highest quality staff, and be able to offer great breadth and diversity of choice, subject and extra-curricular activity. But those schools that are not able to cope with these demands of structural change, exacerbated by continuing and dramatic budget cuts each year, are having their governing bodies excised and school leaders dismissed at an ever increasing frequency. The net effect is high staff turnover, low aspiration in achieving anything outside of the explicit demands of the ‘test’ and a general lack of confidence that the school more generally can meet all of its pupils’ needs. Suggesting now, as the Government’s Green Paper (November 2016) does, that the way forward involves further dramatic structural change, leading to the expansion of grammar schools at the expense of the other existing schools losing their most able pupils in the process will clearly exacerbate the decline in confidence and breadth of success in such schools. It’s worth noting that in a previous structural change, government insisted Universities were better placed to run schools than local governing bodies. The experiment is only a few years old, but all the evidence indicates the experiment is not going well. Moreover, as Professor Louise Richardson Vice Chancellor of Oxford University has made clear; asking universities to set up free schools is “insulting” to teachers and heads. Speaking to the Today programme on 22 September 2016, Professor Louise Richardson said forcing her institution to establish schools would be a “distraction from our core mission”, and said universities already helped the schools community in many ways, but running them was “not what we do”. and diarist has this to say on the 11 September 2015 (we received his latest book for Christmas): David Cameron has been in Leeds preaching to businessmen the virtues of what he calls ‘the smart state’. This seems to be a state that gets away with doing as little as possible for its citizens and shuffling as many responsibilities as it can onto anyone who thinks they can make a profit out of them. I am glad there wasn’t a smart state when I was being brought up in Leeds, a state that was unsmart enough to see me and others like me educated free of charge and send on at the city’s expense to univeristy, provided with splendid libraries, cheap transport and a terrif art gallery, not of course to mention the city’s hospitals. Smart to Mr Cameron seems to mean doing as little as one can get away with and calling it enterprise. Smart as in smart alec, smart of the smart answer, which I’m sure Mr Cameron has to hand. Dead smart.”

and diarist has this to say on the 11 September 2015 (we received his latest book for Christmas): David Cameron has been in Leeds preaching to businessmen the virtues of what he calls ‘the smart state’. This seems to be a state that gets away with doing as little as possible for its citizens and shuffling as many responsibilities as it can onto anyone who thinks they can make a profit out of them. I am glad there wasn’t a smart state when I was being brought up in Leeds, a state that was unsmart enough to see me and others like me educated free of charge and send on at the city’s expense to univeristy, provided with splendid libraries, cheap transport and a terrif art gallery, not of course to mention the city’s hospitals. Smart to Mr Cameron seems to mean doing as little as one can get away with and calling it enterprise. Smart as in smart alec, smart of the smart answer, which I’m sure Mr Cameron has to hand. Dead smart.”